The objective of our initiative ‘Where are they now?’ is to create a forum or a bridge for German alumni to share their career stories with current students, and for students to ask alumni questions about careers. We kicked off the project in June 2017, by emailing German alumni, asking them if they would be willing to share their career stories with current students of German studies. Response was very positive, with over 15 alumni from a wide variety of careers, inside and outside of academia, indicating their interest in participating.

This project was led by Joan Andersen, as part of her volunteer position as Alumni Ambassador and Executive in Residence. Joan is a German alumna of the University of Toronto, and moved into a career outside of German studies after graduating with a Master’s Degree. Joan conducted a telephone or email interview with each participant with the objective or drafting a 5-8 minute long article profiling his/her career.

We will publish one or two ‘Career Profile’ articles every month which we hope our readers will find informative and maybe even inspirational. We welcome your feedback on this initiative by sending Joan an email at j.andersen.ma@gmail.com

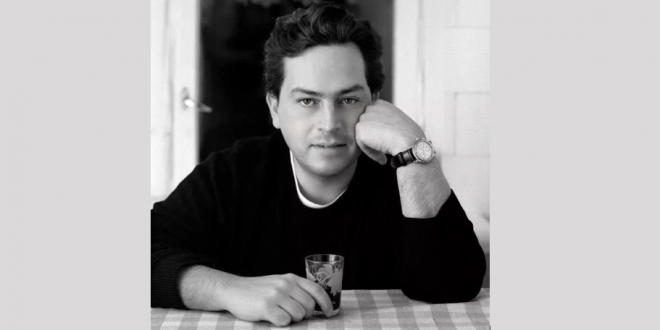

Our second article profiles the career of Luis Fernando Murillo.

Welcome to this edition of ‘Where are they now’? In this article, we profile Luis Fernando Murillo – UofT 1991. I hope you find this article interesting and maybe even inspirational.

Luis graduated from Trinity College at the University of Toronto in 1991, with a double major in Philosophy and Classics, and a minor in German. He received his M.A. in Philosophy and a Ph.D. in Neuropsychology from the University of Fribourg in Switzerland. He taught Human Anatomy in Fribourg and Lausanne, and was a guest researcher at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, and the Ecole Normale Supérieure in Paris, France.

He was named Professor of Psychology and Philosophy at the American College in Switzerland in 2000. He is currently Professor of Psychology at McDaniel’s College in Budapest, Hungary. He is now doing his second Ph.D. in Logic and Philosophy of Science at Eötvos Lorand University in Budapest. Luis has published two books in Germany: one on the ‘Philosophy of Language in late Scholasticism’ and another on the ‘Evolution of Colour Vision’. He has co-authored an article on the ’Functional Architecture of the Visual Cortex’ with Oxford University Press. The National Council for Culture and Arts in Mexico, Luis’ birth country, awarded him a prize for a Spanish translation of Stefan Zweig.

Luis is interested in Philosophical Anthropology, the Intellectual History of Romanticism and the dialogue between Literature and Psychology.

He has also worked as an international teacher and college counsellor in Russia, Ukraine, Azerbaijan, Thailand and China, where he has published numerous articles and interviews with the Shanghai Daily Press.

His passion is classical piano which he studied at the Royal Conservatory in Toronto and at the St. Petersburg State Conservatory in Russia.

We caught up with Luis in Budapest, Hungary.

Read his complete biography in Spanish: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vlXsJajLKdo

1. What made you decide to pursue German studies at the U of T?

My main interest was Philosophy, and German is a very important language for philosophy. For me it was important to find a university where I could learn Greek, Latin, German, and Philosophy. U of T had a renowned faculty in all these areas. I am so grateful to my professors at U of T for the astonishing horizons of thought they opened my mind to. This is especially true of my German teachers: they gave me a passport to not one but many new worlds.

2. Describe your current position and job responsibilities. What career path lead you to your current job?

Presently, I am professor of Psychology at the Budapest campus of McDaniel College. The main campus is based in Maryland. Besides undergraduate teaching on the early History of Experimental Psychology and Psychoanalysis, most of which was published in German, I am also the recipient of a Stipendium Hungaricum grant from the Hungarian government, which allows me to pursue research in Logic and the Philosophy of Science at Eötvos Lorand Univeristy. Additionally, I do a fair amount of educational consulting as a College Counsellor in Europe, Latin America, and Central Asia. In all these tasks, my knowledge of German has proven invaluable.

3. How did you come to select this position as your career?

My current workplace, McDaniel College, belongs to a consortium called the “Colleges that Change Lives”. These are a fairly famous group of liberal arts colleges known for their pursuit of excellence in undergraduate teaching. I get a lot of enjoyment from teaching. It is like story telling. It has a literary and an artistic dimension.

Previously, I had also worked as an international teacher in Asia and in several former Soviet republics. I love teaching. In my mother tongue, Spanish, we have a saying, “he who teaches learns twice”.

4. What made you decide to pursue a career abroad?

Due to my father’s work, my family changed countries several times. I grew up attending international schools where teachers and classmates came from every continent. This piqued my curiosity about other countries. Also, a huge collection of National Geographic magazines at home kept Germany, Sweden, Russia, and Hungary on my mind. As the years passed I have had a chance to study and work in all of these countries. In total I have lived in 14 different countries.

5. What does a typical day at work for you look like?

I like to teach in the early evening, because that gives me the entire day to prepare for a lecture. I make a point of integrating my own current research into my lectures, not least because I strongly believe that my students can give me some of the freshest insights and most interesting perspectives into my investigations.

On days on which I do not teach, I focus on my research, on studying Hungarian, and on my passion, piano.

6. What do you like most about your job?

I love the academic freedom that my University affords me. It is a passport to embark fearlessly on intellectual discovery, and to explore the mind with the greatest honesty. I have witnessed with sadness how that freedom of thought and expression is being eroded in international schools and in North American colleges because of fragile political and religious sensitivities, and that curious contemporary desire not to offend anyone. In particular, the Anglo American world has become more susceptible and prone to censure than, for example, Vienna or Germany at the time of Zweig and Freud.

Respect for others is not synonymous with relinquishing the imperative to pursue an examined life. A stilted discourse and censure is just sterile and conformist. Since Socrates, Western education has been all about questioning certitudes, even if to a certain variety of authoritarians, that is deemed subversive or dangerous. Perhaps that is one of the most memorable lessons I learned from my U of T professors when I studied Plato in the Classics Department and the History of Romanticism in the German Department.

7. What are some of the challenges that you face on a day-to-day basis?

Oh, you mean besides the Hungarian tax authorities….?

8. What skills do you possess that make you a good fit for your current job?

Because I am Mexican, there is a part of me that instinctively resists or at least is not automatically permeable to Anglo-American pop-culture. I think this frees parts of my brain to be naïve and excitable about 19th century Central European narratives, which I receive and relish and try to pass on to others. I am deeply interested in the dialogue between Psychology and Philosophy in this period.

A short time ago, I presented in Mexico, in the presence of representatives from the Austrian Embassy, a Spanish translation of Stefan Zweig’s Erzählungen. Zweig was a close friend of Sigmund Freud and I believe he is a master of the German psychoanalytical novel. He loved and exiled himself in Latin America, distraught as he was by the ravages of fascism in Europe. Latin America continues to love him back.

Another example: several German intellectual movements, from Romanticism and German Idealism to Psychoanalysis and Heidegger have had a fascination with Greek Tragedy and Greek culture in general. The grounding in German and the Classical languages I received at U of T allows me to explore the fascinating and fertile reception of Greek culture in German philosophy, literature, and psychology.

Hence, I feel my training at U of T has prepared me for interdisciplinary and intercultural dialogue.

9. How have your German studies equipped you with the skills you need to do your job?

After my studies at U of T, I worked for a year as a German teacher at the Goethe Institute in Monterrey, Mexico. My knowledge of German allowed me to gain admission at the University of Freiburg in Switzerland, where I did my post-graduate work in Philosophy.

I had the good fortune of meeting Prof. Günter Rager, who was a medical doctor heading the Institute for Special Anatomy and Embryology, but also had a Ph.D in Philosophy. He allowed me, as a philosopher, to do something very Aristotelian: to carry out dissections and explore the inner workings of the body. For the following decade, I researched the physiology of the nervous system with him and with Prof. Robert Kretz, my doctoral supervisor, who had studied with a distinguished Viennese physiologist, Eric Kandel (Nobel prize 2000), and I continued that work in Lausanne and in Stockholm until I received a Ph.D. in Neurophysiology.

During that entire time, I was also a student and friend of Prof. Eduard Marbach, a distinguished philosopher of mind, Husserl specialist, and the former assistant of Jean Piaget.

Thanks to the German I learned at U of T, I was able to participate in the lectures and research of these exceptional mentors, and was able myself to be an instructor at the University of Freiburg, where I taught Human Anatomy and Neuroanatomy.

10. What are your ultimate career goals?

Initially, I was a philosopher interested in the mind. This curiosity catapulted me into Neuroscience research in Europe. Now I have returned to my initial interests in Philosophy of Mind and Philosophy of Language. Along the way, my position as a liberal arts college professor has compelled me to dabble in Sociology and Anthropology. To my delight, I have discovered perhaps more answers to my questions about the human condition in the social sciences than in the interface between Philosophy and Biology. I think my career will slowly crawl towards a better familiarity with social theory.

I remember a beloved U of T mentor, Prof. John Rist, who quoted memorably a passage in Plato, where he describes life and the philosophical enterprise, with the image of a shipwreck survivor at sea clinging to a floating piece of wood, until a larger piece of wood comes along. Ultimately, I also feel like a survivor merely trying to get a better grasp of the world I inhabit, but ultimately that is the only thing I seek, a better understanding of the world around me.

11. What do you do in your spare time?

Philosophy may be my profession, but my passion is piano. It’s a jealous and heart-aching relationship… Life throws a curve ball at you sometimes…

When I finished my Ph.D. in Switzerland, even though I had a professorship, I had to leave the country. The authorities would not renew my student visa, because I was no longer a student, nor would they give me a work visa, because I was not European.

I was heart broken and as I prepared to go teach English in China, I unexpectedly received an answer to a letter I had sent a year back and had long forgotten. I received a letter of admission from the St. Petersburg Conservatory in Russia. Not in my wildest dreams had I imagined that I could ever be admitted to study piano at that institution. But it happened. For two years, until his passing away, I studied with one of the most legendary piano teachers there, Prof. Vasily Alexievich Kalmikov. I also studied History of Russian Music, Music Theory, and Russian. I ended up sympathising with Nabokov, when he said he had a love affair with the Russian language.

Ever since the death of my beloved piano teacher, I have tried and tried, and keep on trying to find a situation where I can combine my academic work, with serious piano study. It’s a dream I keep working on.

12. What advice do you have for German students who are pursuing their studies with the goal of securing meaningful employment post-graduation, outside of German studies (AND, if you have any advice – for those who want to pursue careers related to their German studies or post graduate German studies)?

For those seeking work outside of German studies, I would recommend emphasizing that their German studies demonstrate the ability to take on intellectual challenges and demonstrate intercultural openness.

To all students of German, my main advice is to persevere. After you take your second and third year level courses in German, you might feel frustrated that you are not fully fluent yet or that you can’t pick up every single word in a German movie or newscast. Just keep at it. Read one newspaper article a day. I recommend the Neue Zurcher Zeitung – because it is admirably well written. If you do that you will notice after a semester that you need to look up words in the dictionary less frequently.

Spend time in a German speaking country. Universities in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland are not expensive. Learn as much as you can, read as much as you can. My favourites were Herman Hesse, Max Frisch, Heinrich Böll, Franz Kafka, Thomas Mann and of course Stefan Zweig, which I ended up translating into Spanish. Teaching German to English speakers or teaching English to German speakers was often my safety net when I could not find other employment. There is much demand for this.

For those who want to pursue post-graduate studies, my advice would be to consider my other Alma Mather, the University of Fribourg in Switzerland. As the only fully bilingual university in Europe, it offers the special opportunity to learn German and French simultaneously, and it is undeniable that throughout their intellectual history, these two cultures have cross-pollinated and blossomed together.

13.What advice do you have for graduates seeking positions abroad?

By all means, come to Europe. It is not difficult to come and study here. German is a key that can open many doors, not only in the German speaking world, but also in Hungary, Czech, etc. Get your foot on the threshold using ESL teaching or coming as a student. Once you are in Europe, see what happens. There are many opportunities, Europe is a boundless little microcosm.

14. For those readers who want to learn more, how can they contact you?

Personal email at: luisfernando.murillo@gmail.com

Department of Germanic Languages & Literatures University of Toronto

Department of Germanic Languages & Literatures University of Toronto